I WAS ASKED RECENTLY to address a group of consumer products managers about the possible future of Category Management.

I WAS ASKED RECENTLY to address a group of consumer products managers about the possible future of Category Management.

The request came at a time when I had been devoting serious thinking to several topics that at first seemed only tenuously related. Computer-generated ordering is one. Optimization of markdowns is another. The impact of social, mobile and local media is a third. Then there was this trendy concept — Big Data — that keeps getting lots of mentions, but seems to defy clear understanding.

So what was I to make of Category Management in a world where these disparate forces swirl? More importantly, what practical insights could I deliver to this audience of the best and brightest that CPG companies had on their brand and account teams? I probably couldn’t tell them much they didn’t already know. Maybe I could try to make their heads explode instead.

Thought Experiment

I challenged this audience with the following thought experiment: Try to visualize what life could be like for Category Management professionals in a world with vastly more information and a good deal less control.

The diagram accompanying this post identifies ten factors or sources of input that a Category Manager of the future might incorporate into planning decisions. Many are already familiar — optimization of assortment, price, promotion and markdowns are well-established techniques built into software suites like those from IBM DemandTec. Other vendors offer macro space planning solutions, automated replenishment, capacity planning, In-Store Implementation and competitive analytics. These factors all interact in a dizzying matrix. But wait! There’s more!

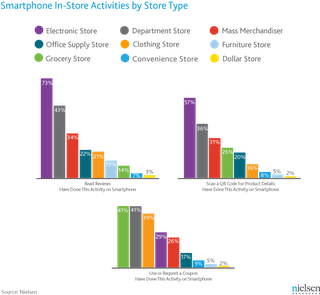

Now fold in the massive influence of social/mobile/local media and online shopping and search behaviors, which are manifest as Big Data. We are witness to the vanishing boundaries of the in-store environment, due to the advent of personal digital technology, changing consumer habits, omni-channel business models and the immense flows of unstructured and structured data that these are creating for Shopper Marketers. I call this The Incredible Dissolving Store.

Big Data postulates that we will soon be routinely mining these external data flows for relevant behavioral insights and applying those insights on a continuous basis to enable shopper success and sustain meaningful competitive advantage.

Mix Mastery

It’s kind of like the marketing mix management problem. Heck, in many ways it’s a core part of the marketing mix problem. Shopper success — and therefore, the success of our category and promotional plans — are influenced by all these factors. Simultaneously. Continuously.

The increasing intricacy of the merchandising decision process reflects the proliferation of intersecting, measurable and optimize-able factors within the store. All these new data-based influences mean the locus of power is rapidly leaving the store and distributing across your customers’ mobile devices. The shopper is always in the center — no matter where you go, there they are.

It becomes increasingly apparent that Category Management in the Incredible Dissolving Store will not be about solving the equation — it will be about tuning the system. New analytics tools make the keys to relevance more accessible and more automated than ever. The life cycle of your decisions, shorter than ever. The power resides in the network and in the hands of individual shoppers.

Category Management, like it or not, is rapidly shifting from an orderly, controlled, recursive, planning process with boundaries and well-defined metrics into a deliberately dis-orderly, multidimensional, broad, shape-shifting and organic process that incorporates planning, detection, response and continuous strategic reconsideration.

In the Incredible Dissolving Store, we need to get used to the kind of ongoing discomfort this implies and think very carefully about the metrics we use to define success. If we listen actively and shed our bias, the shoppers will tell us what those must be.