|

| Is this shelf set correct? |

IN MY ROLE as Director of the In-Store Implementation Network, the challenge of merchandising compliance is frequently addressed, from a variety of perspectives – both theoretical and solution-oriented.

Several recent conversations have centered on the question of measuring the accuracy of a shelf set; that is, its degree of compliance with the schematic or planogram. This is actually a non-trivial matter when seeking a practical solution. Since a planogram is a complex tool covering many details (items, facings, positioning, quantities, etc.) determining what data to measure, how often and to what end(s) requires a thoughtful process.

Our valued colleague Mike Spindler, CEO of ShelfSnap has championed this discussion in several items posted on the ISI Network LinkedIn Group page. He is one of the better thinkers we have on this topic, and his company offers a promising tool for digitally comparing an image of an actual shelf set with its associated planogram.

How Close is Close Enough?

If the comparison is “perfect” – that is, all item are present in their proper locations and quantities – we can safely declare that a shelf set is compliant with the plan. This is, however, a rare occurrence which probably exists only for a few minutes after the re-set work is correctly completed. The moment shoppers get to removing items into their baskets, perfect compliance begins to deteriorate. Darn those pesky shoppers!

As I like to say, the “half-life” of a typical shelf set is less time than it takes the re-set crew to leave the building. A slight exaggeration, maybe, but you get the point.

So when do retailers declare a merchandise set to be “out of compliance”? When 9% of items are out of stock (the industry average in grocery)? When 15% of items are present but mis-located? When the number of facings is off on more than 25% of items? Alternatively, what criteria define “in compliance”? All items present and accounted for? 90% of items in the correct place? 99% in-stock? How close is close enough?

Evidently, the ways a planogram can go wrong are numerous but not always numerical. More significantly, they are not easily recognized by human inspection. That is, compliance issues can be hard to spot without a scorecard in hand – and even then it takes concentration and focus and time.

Compliance Shorthand

What if we could define a short-hand method instead – perhaps three to six yes/no metrics that could be taken as a proxy for overall compliance? ISI Network member Larry Dorr, a respected expert on retail merchandising and founder of Jaguar Retail Consulting, described an approach that is worthy of discussion.

He proposes measuring the condition of approximately five or six “destination” items for each category or major subcategory. These are often the highest-velocity items in their respective sections. “Measure the items adjacent to those items,” he says. “If those five and their adjacencies are in correct shape, then the set is probably in good shape overall. If two of the five items are off, you may assume a compliance problem.”

This approach offers economy, speed and ease of implementation. A limitation, he concedes, it that this doesn’t provide a measure of item distribution. While the five-item rule may deliver a directionally correct conclusion about planogram compliance, it may not help very much with gauging the performance of non-destination items.

Also worth noting is how the criteria for compliance may vary across different product categories and classes of trade. Our example above is drawn from a grocery/mass perspective. In specialty apparel and department stores, where color, size and style factor in, the definition and metrics for compliance will differ. Consumer electronics retailers will face their own compliance issues.

Storecard Metrics Needed

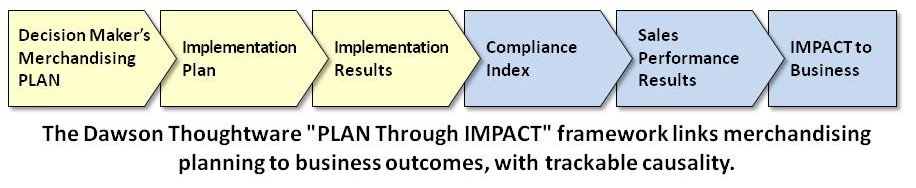

So let’s grant that merchandising compliance is a slippery quantity using presently available methods. That doesn’t absolve practitioners from the requirement that they track and measure merchandising performance. In fact innovation in Shopper Marketing, segmentation and automated planograms only intensify the need.

We need creative thinking and some consensus on what constitutes compliance success; on what to measure, how and how often. The goal is to define some compliance best practices and incorporate the metrics into in-store scorecards – what I like to call storecards – that support and enable those practices.

Which leads me to offer this challenge: Use the comment form on this post or on the ISI LinkedIn Group to help us define: What constitutes merchandising compliance? How do you/should we measure it? What are the thresholds? How good is good? What’s the cost of good?

This could be the first step along the road to In-Store Implementation Best Practices. I look forward to reading your thoughts.