Tenser’s Tirades recently sat down with Warren Dawson, President of consultancy Dawson Thoughtware, for a conversation about his vision for a comprehensive framework for what he calls Merchandising Resource Management, designed to support superior store-level compliance and effective measurement methods, from initial plans to their ultimate impact on business. The MRM process allows retailers and suppliers to set objectives, measure performance at each process stage, and gauge the impact these have on the overall business.

Dawson was instrumental in organizing the In-Store Implementation Sharegroup and a contributor to its 2008 working paper. He is preparing a new paper, “Plan Through Impact,” that outlines his point of view regarding the next wave of innovation in supermarket store operations, one he believes opens up great opportunities to improve both shopper experience and financial performance.

TT: Warren, you’ve earned a long-standing reputation as one of the visionaries in supermarket merchandising, especially space and assortment management. What’s driving you to speak out again about merchandising compliance?

WD: It’s no secret that I’ve been an advocate along these lines for many years. I started working on the core issues of store-level item distribution in the 1980s. I’ve had the opportunity to help many supermarket and CPG companies tackle space and assortment issues since then. The idea behind the ISI group was to bring together a credible group of companies and industry people to debunk the myth that all is well with In-Store Implementation.

While we’ve seen improvement in supply chain methods, category planning and demand-based insights, the in-store opportunity remains vast – tens of billions of dollars in missed sales, billions in profits. As the ISI Sharegroup working paper showed in 2008, we have barely budged in 20 years on core issues like item availability, promotion compliance, speed to shelf and planogram integrity. I think we have the means to fix those things today.

TT: What do you mean by “Plan Through Impact”?

WD: Well, besides persistent irritants like out-of-stocks and poor promotion compliance, two areas of change in merchandising planning in the grocery industry have brought this need to a higher urgency: The first is Shopper Marketing, which has led to a much greater degree of segmentation and targeting around in-store merchandising and messaging. The second is the adoption of planogram automation tools, which permit retailers to vary merchandising plans down to the store level, if justified by shopper insights.

TT: Those sound like positive developments. Are you skeptical about their value?

WD: Not at all. It’s great, must-do stuff. The challenge is that they introduce an enormous amount of additional intricacy that the industry is not well-prepared to manage. Retailers and CPGs are getting a lot better at formulating subtle and insightful plans, but they lack the know-how and every-day practices to carry those plans out effectively in the stores. There’s a huge risk of wasted spending.

TT: Isn’t that what Workforce Management and Store Execution Management software is supposed to address?

WD: Yes in theory. And these types of tools are likely to be parts of the Merchandising Resource Management solution I envision. They let us formulate a compliance plan and push it out to people in the field. But organizing and communicating tasks is just the first step in the process. There has to be a process for confirming that the tasks get done, measuring them and comparing them to expectation. And you have to be able to share the results to all participants in the process, so they can manage their own performance.

TT: Sounds a lot like the “Plan-Do-Measure” concept advanced by the ISI Network.

WD: Exactly right, although MRM goes further. You need an embedded feedback loop to monitor compliance. Regularity in the information will ultimately help trading partners make better, more realistic merchandising and promotion plans. It’s foolish and costly to plan work that doesn’t get done, and yet that’s what we do every day, because without measurement tools we can’t visualize how our unrealistic plans damage our business outcomes.

TT: So how does “Plan Through Impact” extend this thought process?

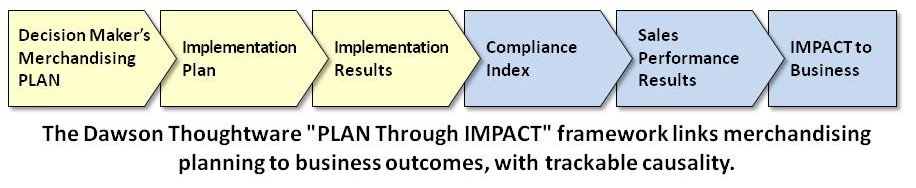

WD: By adding three more levels of measurement. Its core is what I call a Compliance Index that synthesizes several store-level metrics into a score that can be rolled up from the item level all the way to the category, cluster or account level. Then compliance must be linked to what we all care about – sales performance results. Finally, we need to connect the dots to measures of business impact – customer experience and loyalty, competitive position, and shareholder value. I sometimes like to call this “Plan-Do-Measure-Measure-Measure-Measure.”

TT: Are you suggesting that we establish a chain of causality connecting a company’s shareholder value all the way back to its merchandising competency?

WD: I believe it’s an achievable goal. Merely tracking merchandising outcomes doesn’t provide a reliable proxy for business performance. We feel intuitively that compliance must have an impact, but we can’t use it to support strategic decisions unless we establish a Plan Through Impact framework.

TT: Sounds challenging. Aren’t you asking for too much?

WD: At one time this might have seemed beyond us, or at least prohibitively costly, but today we have all the elements within our grasp. There’s no shortage of tools to support store level measurement and communications. In fact, many merchandising field organizations are already heavily invested in portable technology with verifiable self-reporting that would support a viable compliance index. Then there are the point solutions for digital image analysis, out-of-stock detection, spot audits, and demand signal analysis to name a few.

TT: If those software and hardware tools are already available, why isn’t the industry already enjoying greater success?

WD: Because they are being put into use ad hoc, and in the absence of a crucial thoughtware layer. Merchandising Resource Management is a business process, not a technology. It requires some changes in business practices at the store level, as well as for decision-makers and administrators. Also, because it creates greater transparency of compliance performance, it has potential to change the way trading partners collaborate for success. Most companies are going to need a little help putting this into practice.

TT: How can companies educate themselves further about this?

WD: Interested parties are welcome to email me at WarrenDawson@gmail.com for a copy of the paper or to discuss a consultation. A good place to begin reading is the In-Store Implementation Network site. Many downloads are available with free registration.

© Copyright 2009 James Tenser